PAIN MANAGEMENT

Pain perception during uterine aspiration is a complex phenomenon influenced by both physical and psychosocial elements, and can vary considerably between individuals. The table below summarizes the research on factors associated with pain during uterine aspiration. In the multivariable analyses, no single factor predicts procedure-associated pain (Singh 2008) and every person deserves a discussion of pain control options.

Additionally, implicit and explicit biases regarding age, race, body size, weight, current or past substance use disorder, and use of medication for opioid use disorder have been shown to contribute to provider perception of a person’s pain and subsequent treatment decisions regarding pain management (Mende-Siedlecki 2019; Sabin 2020; NAF CG 2022). A meta-analysis on pain management including 20 years of data found that Black patients were 22% less likely to receive pain management than white patients, and the size of the difference was sufficiently large to raise not only normative but quality and safety concerns (Meghani 2012). To improve patient care and equity, providers should work to identify and minimize their own biases, which may include unlearning of prior practices.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH PAIN DURING UTERINE ASPIRATION

| Increased Pain | Decreased Pain | Conflicting Results | Not Strongly Associated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety/depression

Ambivalence Expectation of pain Younger patient age Dysmenorrhea Fewer pregnancies |

Previous vaginal delivery

Older patient age More pregnancies Shorter operative time Participation in the |

Gestational age

Max cervical dilation Comfort with decision Provider experience |

Prior pelvic exam

Prior uterine aspiration Prior cesarean section Manual vs. electric vacuum aspiration |

NON-PHARMACOLOGIC PAIN MANAGEMENT

Many people have anxiety about anticipated pain. Supportive verbal communication, including distraction and so-called “vocal local” or “verbicaine”, can play a role in reducing anxiety and pain. Providers can acknowledge the possibility of pain while offering strategies to manage it. Offering elements of positive suggestion may help to allay concerns. For example:

“It is normal to be worried, and often people are surprised that the procedure is faster and more tolerable than expected. Pain can vary, but slow deep breathing helps, and I’ll give you some numbing medicine and be as gentle as possible.”

Guiding patients to take slow, deep, regular breaths can assist in reducing anxiety, avoiding hyperventilation, and also give an increased sense of control. Encourage patients to release their hips into the table instead of pulling away and tightening.

Guided imagery can also decrease anxiety and analgesic requirements for surgical patients (Gonzales 2010). Consider encouraging patients to recall a favorite place, activity, or color, during the procedure. Relaxing images or mobiles above the exam table have also been used to decrease pain and anxiety during gynecologic procedures (Carwile 2014). Playing music in the room may be helpful with anxiety and satisfaction, but does not decrease pain (Wu 2012, Guerrero 2012, Cepeda 2006). A heating pad or hot water bottle may be helpful during the procedure, in recovery or at home. A support person of the patient’s choice can also improve their abortion experience (Altshuler 2021). For additional considerations, see the RHAP Contraceptive Pearl (Ti 2022).

CHOICE OF PAIN MANAGEMENT METHODS

Discussion of pain management options should be reviewed as part of the informed consent process, including the range of possible experiences, available options for pain management, as well as their risks and benefits. If someone has a strong preference for an option your facility does not offer, an appropriate referral can be given.

Premedication with NSAIDs has been shown to decrease pain during and after the procedure, and has few contraindications or side effects (Ipas 2021). Some people choose this option to be more alert, have shorter recovery, or to drive themselves home.

Other patients may choose more sedating options to reduce pain and anxiety, to induce some degree of amnesia, or to manage a later procedure. Oral opiate analgesics have shown minimal effect on pain compared to placebo and cause more side effects including nausea (Micks 2012). IV sedation may be offered in some settings for people who request more analgesia, although some medical conditions, monitoring, or facility limitations preclude moderate or deep sedation. Deep sedation can be used, but is not routinely recommended (Ipas 2021).

PROVIDING EFFECTIVE LOCAL ANESTHESIA

Local anesthesia options include paracervical block (PCB) and vaginal lidocaine.

Below are techniques and pitfalls of paracervical block, preparations, and injection.

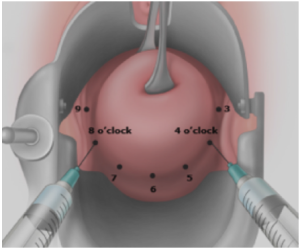

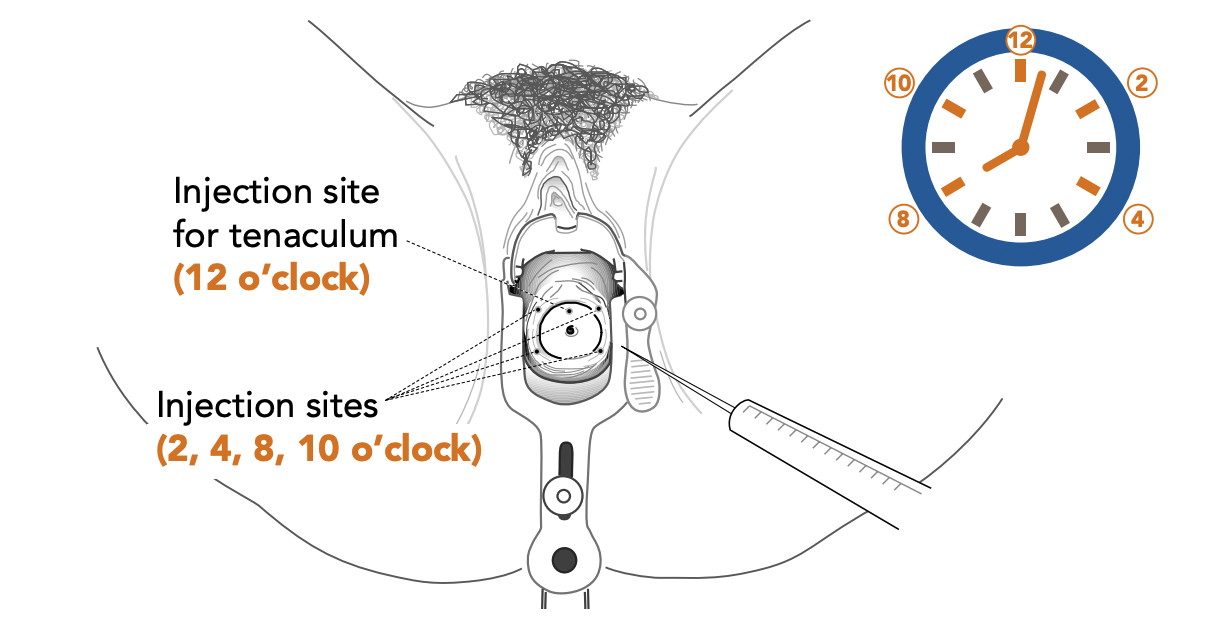

- Paracervical block (PCB) is effective at reducing pain, although injection can be painful (Renner 2012). Injection locations and techniques vary by provider.

- A four-site PCB appeared to be superior to a two-site PCB (Renner 2016).

- Reported pain scores during dilation and aspiration are improved with 20mL buffered lidocaine and deep injections (1.5 to 3 cm) (Renner 2010, Moayedi 2018).

- Slower injection (30 sec vs. 120 sec), smaller needle diameter (e.g. 25 gauge), or injecting ahead of the needle may decrease pain.

- Some use cough technique during injection, but data is limited (Lambert 2020).

- Local anesthetics block nerve impulses, and volume causes tissue distention, separating nerve endings, providing some analgesic effect.

- Saline has less effect than lidocaine (Chanrachakul 2001).

- Ketorolac in block decreased dilation pain, but not overall pain (Cansino 2009).

- No evidence suggests one anesthetic is superior; options are reviewed below.

- No study demonstrates complete pain prevention with local anesthesia, some providers test with light stimulation, adding additional anesthesia if needed and safe.

|

|

|

|

|

| One approach is to inject 1-2 mL at 12 o’clock for the tenaculum, and then inject at 4 and 8 o’clock as depicted above to target paracervical innervation. Other approaches are to inject at 2 and 10 o’clock, or 3 and 9 o’clock. Images: Vidaeff 2016 & Ipas. |

Self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel is noninferior to PCB in first trimester procedural abortions, and may be considered as an alternative, noninvasive approach to pain control (Conti 2016, Liu 2021).

TIPS TO MINIMIZE SYSTEMIC ABSORPTION

The most studied maximum dose of lidocaine in pregnancy is 200 mg [achieved for example, by giving 20 ml of 1% lidocaine (10 mg/ml)]. A study of paracervical block combined with intrauterine lidocaine in pregnancy found a dose of 300 mg was safe, but with more systemic side effects (Edelman 2006). A maximum dose of 300 mg of lidocaine is typically recommended for any local anesthetic use. With IV injection, people may experience peri-oral tingling, dizziness, tinnitus, metallic taste or irregular/slow pulse. At higher concentrations, they may have muscular twitching, seizure, cardiac arrhythmias, unconsciousness, and even death (Paul 2009).

- Minimize direct intravascular injection and excessive anesthetic dosing.

- Use a combination of superficial (1 cm) and deep injections (3 cm).

- Move the needle while injecting (superficial to deep) and/or aspirate before injecting.

- Use a dilute concentration (using 0.5% lidocaine or diluting with saline).

- Use a vasoconstrictor mixed with the anesthetic to slow systemic absorption.

| Generic (Trade) | Potency | Onset | Duration | Max Dose (mg) without episode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bupivicaine (Marcaine) | Strong | Moderate (up to 20 min) | Long (3-6 h) | 175 mg |

| Lidocaine (Xylocaine) | Medium | Fast (4-7 min) | Moderate (1-2 h) (~3 h with epinephrine) | 300 mg |

| Mepivicaine (Carbocaine) | Medium | Fast (4-7 min) | Moderate (3 h) | 400 mg |

| Chloroprocaine (Nesacaine) | Weaker | Fastest | Short (30 min) 25 sec half life | 800 mg |

UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS

To prevent transmission of blood-borne pathogens, universal precautions include:

- Glove and use protective eye wear when working with body fluids (i.e. injection, procedure, handling of tissue or contaminated instruments).

- Avoid recapping contaminated needles, and place sharps immediately in a puncture-resistant container for disposal.

- For blood exposure, inform your supervisor, and consult National Clinicians’ Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline.

CONTINUUM OF SEDATION LEVEL

Various approaches to pain management may be offered, depending on the clinical situation and resources. Below is a short summary of the levels of sedation, examples of medications used, and the associated risks.

| Level of Sedation | Example | Responsiveness | Airway | Spontaneous Ventilation |

Cardiovascular Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (Anxiolysis) | Oral lorazepam and/or hydrocodone |

Normal response to verbal stimulation |

Unaffected | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Moderate “Conscious Sedation” | Fentany +/- Midazolam |

Purposeful response to verbal or tactile stimulation | No intervention required | Adequate | Usually maintained |

| Deep | Add propofol or higher doses of meds used for moderate sedation | Purposeful response following repeated or painful stimulation | Intervention may be required | May be inadequate | Usually maintained |

| General Anesthesia | Propofol or other medications | Unarousable even with painful stimuli | Intervention often required | Frequently inadequate | May be impaired |

Adapted from Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of GA and levels of Sedation / Anesthesia, ASA 2019.

MONITORING GUIDELINES

- During moderate sedation, a person trained to monitor cardiorespiratory and level of consciousness must be present, other than the provider.

- Moderate sedation may lead to deep sedation with hypoventilation, so providers must be prepared to provide respiratory support (ASA 2019).

- Pulse oximetry should be used to enhance monitoring.

- IV access should be maintained.

- Verbal responsiveness should be checked frequently.

- For patients with severe systemic disease, a higher level of care should be considered

- When moderate sedation is used, monitoring must be of a degree that can be expected to detect the respiratory effects of the drugs being used.

- The practitioner administering deep sedation or general anesthesia must be certified according to applicable local, hospital, and state requirements.

CONSENT CONSIDERATIONS PRIOR TO SEDATION

Obtaining informed consent should occur prior to initiation of sedating medications. If a patient is drowsy or unable to answer orienting questions, consider having them rest awhile and reevaluate for consent. Substance use disorder history, and use of MAT medications does not alter the informed consent process; in fact withdrawal symptoms may impede proper consent. It is also important to use verbal consent throughout the procedure as is recommended with trauma informed care.

Techniques for evaluating if patients are able to consent for a procedure include asking orientation questions and having patients repeat information back after reviewing it, with the following key considerations of medical decision making capacity. Patients must be able to:

- demonstrate an understanding of risks, benefits and alternative options

- demonstrate an appreciation of those benefits and risks

- shows reasoning in making a decision

- communicate their choice